Eisenstein’s "October": Between Artistic Invention and the Myth of the Revolution

October is the final installment in Sergei Eisenstein’s historical-revolutionary film epic, which began with the films Strike (Stachka, 1924) and Battleship Potemkin (Bronenosets Potemkin, 1925). The trilogy uses a new film language to portray the events of the revolution as a painful and unavoidable “tectonic shift” in history, and it does so without the support of traditional plotting, psychological insights, or individual characters. Today Eisenstein’s films can be understood as an ingenious and politically oriented mythologization of historical events, and also as a work of artistic discovery, a parable about the nature of power and social violence.

October was created at the behest of the October Anniversary Commission of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR. Only a small group of directors were trusted with the creation of celebratory artistic films about the revolution. Vsevolod Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg (Konets Sankt-Peterburga) and Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October (Moskva v Oktiabre) also appeared on Soviet movie screens in 1927. Yet Eisenstein’s October stands out as the most ambitious Soviet film project of the 1920s, even though less than a year was allotted for the film’s creation. Having received the commission, Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov suspended work on The General Line, a film about collectivization, and quickly began gathering materials about the “Ten Days that Shook the World” (the original title of both the script and John Reed’s book, one of the sources used in preparing the film).

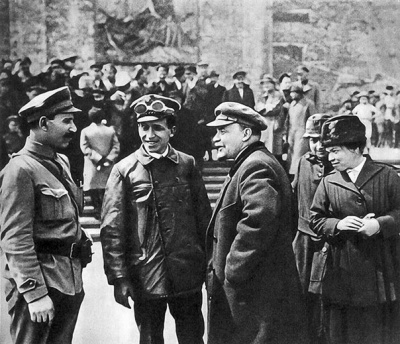

“A Hundred-Thousand-Strong Army before the Movie Cameras”

|

|

|

| Stills from the film |

Filming for the anniversary film epic began only in April 1927. The style of the film’s organization, which can be described as “revolutionary art in action,” still fires the imagination no less than the film itself does. The filmmakers had at their disposal an array of resources and privileges unprecedented for that time. As Eisenstein wrote, they achieved the “penetration of cinematography into everyday life.”

“For that half-year we worked in Leningrad. In my opinion, that city has every reason to be displeased with us. We fought against its present habits and its present life… We struggled with the people, forcing them back ten years into the past.”

(Citation here and below from: Sergei Eisenstein, “V boiakh za “Oktiabr’” [In the Battles of October],” Komsomolskaya pravda, March 2, 1927).

Searching for “character types,” the “assistants caught people who had the right appearance, who suited the part, and demanded unquestioning submission.”

During the daytime throughout the city bridges were drawn, trams were stopped, and in certain areas the electricity was cut off. A double load of ammo was used in filming the historic shot fired by the Aurora (to ensure that the flame would be visible on screen) and the windows of many buildings on the Neva embankment were shattered. Believing a salvo from the battery of the Peter and Paul Fortress to be a flood warning, city residents rushed to secure their possessions. Some say that filming the storming of the Winter Palace caused more damage to the building than had the original events of November 7, 1917…

Although the picture was completed in half a year, Eisenstein believed that the process should have taken a year and a half; this is, Eisenstein’s words, the “most modest estimate.” He remembered the filming as six months of sleepless nights, as “life in the fourth dimension.”

“Sometimes we filmed for sixty hours without respite … We slept on cannon carriages, on the pedestals of monuments, … in the assembly hall at Smolny, by the gates of the Winter Palace, on the steps of the palace’s Jordan Staircase, in automobiles (the best sleep!) … The rest of the time we filmed. Altogether, we shot about a thousand scenes. I don’t remember precisely how many.”

All told, 49,000 meters of film were used to capture a massive quantity of material, but only 2,000 meters made the final cut. The original plan had been even more grandiose: the film was meant to depict the entire period from the February Revolution to the end of the Civil War. The completed version included only scenes of the February Revolution, Lenin’s arrival at Finland Station, the shootings at the July 4th demonstration, the Kornilov affair in Petrograd and General Krymov’s Savage Division, the storming of the Winter Palace, and the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

“Cut out Trotsky!”

The premiere of October was scheduled for November 7, 1927. Grigori Aleksandrov recalled that on that very day Stalin appeared in the editing room and ordered the immediate removal of all scenes featuring Trotsky (Epokha i kino [Era and Film], 1983). As it turned out, that morning during the anniversary demonstration, detachments of the State Political Directorate (GPU) suppressed an attempted “uprising” by the “Trotskyite opposition.”

Thus, the anniversary film presented that day in the Bolshoi Theatre was fragmentary, as it could not be shown in its entirety. It took another several months to reedit and finish the film. Finally, in March 1928, Sergei Eisenstein announced:

“October—a film difficult both in mission and realization, a film that must communicate to the viewer the powerful pathos of the days that shook the world, that establishes our new approach to filming objects and events, that influences the viewer with filmic art’s difficult new methods, that demands sharp and breathless attention—is completed. Now the viewer will be the judge!” (“In the Battles for October”).

The newspaper Pravda grandly announced: “100 cinemas in the RSFSR are simultaneously presenting the revolutionary war film October.”

After 1933, the film vanished from cinemas, although it was still lauded a classic of Soviet cinematography. Evidently, there was no place to insert Stalin’s image into October, and the film’s depiction of Lenin was unsuccessful (the role was played by a worker named Nikandrov, who Eisenstein selected solely on account of his physical similarity to Lenin). Mikhail Romm’s Lenin in October (Lenin v Oktiabre, 1937) was released in time for the twentieth anniversary of the revolution. This film established a new model for Soviet historiography: the revolution succeeded not on account of the “revolutionary masses,” but thanks to two leaders, Lenin and Stalin.

“A Catalogue of Inventions”

Eisenstein believed that his films (and new, revolutionary Soviet cinema in general) should “plough up” the viewer’s psyche like a tractor. Throughout the 1920s he worked on developing a theory of film that would break new ground by directly influencing the viewer’s consciousness.

Strike and Battleship Potemkin embodied the “montage of attractions” theory, aggressively emotional shots that shock the viewer and evoke the director’s chosen emotion. The classic example of this method appears in Battleship Potemkin with the cruel execution of unarmed people on the Odessa Steps. For Eisenstein, the scene of the bridges being raised during the dispersal of the July demonstrations represented October’s “Odessa Steps.” This episode also features a series of images that show violence against unarmed demonstrators (the corpses on the square, civilians mocking an injured Bolshevik, ladies stabbing him with their umbrellas, the murdered woman, and the dead horse hanging over the water).

In October, an “intellectual montage” complements the “montage of attractions.” This meant using a succession of images that would call up certain associations and concepts in the viewer’s mind. For example, in the Congress of Soviets scene, Eisenstein placed the Menshevik’s speech alongside shots of a musician strumming the harp, and after the Socialist Revolutionary’s speech, a balalaika appears on screen (alluding to this group’s claim to being the “peasant” party). The musical instruments were intended to serve as metaphors for the orators’ palliative or empty-headed speeches (although, as the Soviet critic and film expert Nikolai Lebedev noted, these images would confuse the average viewer: why were musical instruments popping up at the Congress of Soviets?). In contrast, the Bolshevik who appeared next on the rostrum had his words validated through their juxtaposition with gunfire.

The classical example of “intellectual montage” is the toppling of a series of Gods, from Christ to ritual masks and pagan deities, which takes place during Kornilov’s march on revolutionary Petrograd. Subsequent shots show epaulettes and cross-shaped medals, intended to symbolize the notion of the “homeland.” According to Eisenstein, these figurative sequences were meant to diminish the pathos of the monarchical slogan, “for God, for faith, for the Fatherland.”

The film October was ripe with innovations in the sphere of film language. The director made the screen pulse and explode in the viewer’s consciousness, as the images on the screen conflicted with, yet paradoxically complemented, one another. For many more years, Eisenstein used his theoretical works and lectures for student cinematographers to convey detailed explanations of the innovations in editing and montage he accomplished during the making of October.

“Crude Tricks”

These experiments evoked a wide variety of reactions from critics, party workers, and “colleagues in the film studio.” After the premiere of October at the Bolshoi Theater, Vsevolod Pudovkin, according to Viktor Shklovsky, stated:

“How I would have loved to have such a forceful failure at some point. From this day forward we shall work differently.”

The fundamental complaint revolved around the film’s “artificiality” and its “superfluous effects,” which were unacceptable in a film dealing with such a meaningful topic and which proved incomprehensible to the average viewer. For example, Nadezhda Krupskaya, who served as a consultant on October, fully acknowledged the film as a “piece of the art of the future,” but also remarked on the depiction of the shootings at the July demonstration:

“Crude tricks will not do. The dead horse suspended over the water, hanging from the shafts of the opening bridge; the murdered woman’s hair spreading out, covering the bridge’s slats. It’s too much like an advertisement, it’s theatrical.”

Theorists at the journal LEF (Left Front of the Arts) mounted the most extreme attack on October, as they remained firmly committed to the “literature of facts” and the “montage of facts” in film. In his articles, Osip Brik called attention to Eisenstein’s numerous departures from reality. For example, he considered the satirical over-dramatization of the activities of the Women’s Battalion of Death to be deliberate and even tactless, all the more because these female shock troops, abandoned to defend of the Winter Palace, actually played a rather small role in the October events. The scene in which sailors smash a pile of wine bottles and prevent the population from pilfering the royal wine cellar, Brik called poster-like and deceitful, stating that the sailors’ battle in the wine cellar after the revolution was one of “October’s murkiest episodes.”

Esfir Shub, director of The Great Way (Velikii put’, 1927), a newsreel documentary about the revolution, wrote an article about October with the telling title, “This Work Shouts”:

“Do not dramatize historical fact, because dramatization distorts fact.

Do not replace Vladimir Ilyich with an actor whose face appears similar to Vladimir Ilyich’s.

Do not allow either the millions of peasants and workers who have not participated in battles, or our next generation—the Komsomol members and the Pioneers—to think that the events of those great days followed the course of Eisenstein and Aleksandrov’s October.

In such matters we need historical truth, fact, documents, and a great strictness in realization—we need a chronicle.”

Viktor Shklovsky gave the most balanced evaluation of the film. In his 1927 article, “Errors and Inventions [Oshibki i izobreteniia],” he suggested that one should not compare this film to a chronicle, because each represents a different creative mode. Eisenstein’s October is distinguished by its “perfectly ingenious freedom in reference to things,” and, regardless of the incorrect manner in which the task was completed, the “catalogue of inventions” remains the film’s primary accomplishment. He also noted with irony that if it had not been for the revolution, Eisenstein and Pudovkin would have both been “wild aesthetes.” Their attraction to experimentation demanded precisely that moment in history, which afforded them the opportunity to create uncompromising and authentically “Bolshevik” works.

The German film expert and critic Siegfried Kracauer wrote the most notable Western reviews on Eisenstein. He spoke rapturously about Battleship Potemkin, calling it “true art” and a film breakthrough that moves toward “real history.” Kracauer saw Eisenstein’s next film, October, as Soviet propaganda:

“Eisenstein’s Ten Days that Shook the World is an official picture about the revolution. Obviously, it was filmed on the order of the Soviet government, to disseminate the history of those memorable days throughout the cities and the population. It presents the officially approved history lesson: Kerensky was like this, Kornilov was like that, and this is how we are. The citizens walked there, and ours stood at that post. It should be said that, in some places the illustrators treated history too freely for our taste. Why was it necessary to portray Kerensky as such a coward? Did the film really require the episode in which the Junkers steal spoons? From our point of view, with these details the pictures’ makers only discredited their own creation.” (S. Kracauer, “Articles about Soviet Film” [in Russian]).

Such suspicions about Eisenstein’s political commitments have come up again in the course of the post-Soviet revision of the legacy of the Soviet period. The director is increasingly seen as a “totalitarian artist” and a falsifier of history, whose relationship to the viewer embodies all of the cruelty of Soviet rule, which used an iron fist to create a population of “new people.”

From Metaphor to Mythology

October begins with shots of the destruction of a statue of Alexander III (in one of his notes, Eisenstein wrote that he had long been dreaming up a “widow” for this monument, and could not resist the temptation; after all, he thought, “what is history without the guillotine?”). In reality, the monument, unveiled in a grand and public manner near the Church of Christ the Savior in 1912, was torn down in 1918 in accordance with the new government’s decree, “On the Destruction of Monuments Erected in Honor of the Tsar and his Servants.” Many viewers would have remembered this, and therefore the shots of the destruction of the unwieldy memorial were obviously symbolic, not “historical” (in the “Kornilov revolt” sequence, it emerged from the wreckage before the viewer’s very eyes). In fact, at the very beginning of this film about the revolution Eisenstein asserts his right to relate freely to the material at hand. His main task was in itself artistic: to create a “100% emotionally gripping” film, such as Battleship Potemkin.

Soviet history, however, dealt with October in its own way, granting many of its episodes and images a documentary character. For example, still shots of sailors at the Winter Palace’s iron gates appeared as illustrations in Soviet history books (later these images were repeated in Romm’s Lenin in October and this strengthened their “documentary” nature). In reality, the gate had been open, but Eisenstein believed in the importance of the symbolism inherent in the images of the sailors stepping on the imperial crest.

Today’s historians have demonstrated that the Winter Palace was taken with considerably less force than is shown in October (it is no accident that in the 1920s the events of November 6-7 were legitimately called “revolutionary”). For Eisenstein the mass character of the storming of the Palace in October was a meaningful part of his social epic and represented the trilogy’s artistic finale. The cruel episodes depicting the dispersal of demonstrators in Strike and October, as well as the shooting of peaceful citizens in Battleship Potemkin, embodied the sacrifice and despair of the lower classes, who the regime treated like “cannon fodder” (Strike provides a direct allegory, as the dispersal of the demonstration is juxtaposed with the slaughter of cattle). In October, the crowd is transformed into a “revolutionary mass,” which alters the course of history.

Taken together, this all creates the impression that the “old world,” with its pomp and pathos, sickened Eisenstein stylistically. In the spirit of the times and as an avant-garde artist, it did not sadden him to destroy this “dead world.” Shklovsky, as a man of the same artistic era, understood Eisenstein’s moods well. In his novel Eisenstein, he wrote:

“October is a reel about the end of things, about another world, and at the same time it depicts the old world through its trappings…”

The imperial family’s personal belongings play a role in a series of scenes in October, and the director brings down all of his irony and sarcasm upon these objects (for example, in the “Tsarina’s Bedroom” sequence, the sailor watches as icons, Easter eggs, clay pots, a bidet, an erotic sculpture, and a china pig “exchange glances”; Eisenstein identified revulsion as this episode’s main emotion).

Eisenstein thus interprets the beginning of the march on the Palace as the beginning of a new age, one that arrived at midnight, during the zero hour (and it is not so important that he “adjusted the clock,” as the historical storming began after 1:00 am). In the film’s finale, all the world’s clocks herald the birth of a new world.

October in the History Classroom

Proving the following thesis could become a central task in working with materials about the 1917 revolution as part of a history lesson:

The sequence of revolutionary events was established long ago, but facts themselves do not make up our knowledge of the past. They are superseded by interpretation and choices made in the language of their description. This problem remains important today. What happened on October 25 (November 7) 1917: a coup d’état, a Great Socialist Revolution, a popular uprising, or was it the chaos of a power vacuum, which the Bolsheviks exploited?

Historical reality exists only as an aggregate of perspectives, and memoirs about that period demonstrate that these points of view do differ (during a lesson, for example, a comparison could be made between excerpts from John Reed, Leon Trotsky, the memoirs Defense of the Winter Palace (Zashchita Zimnego dvortsa) by White officer Aleksandr Sinegub, and others).

Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov’s October is just one version of historical events. In the classroom, this film raises many “problematic” themes and timely questions (also, thanks to its complexity, October can serve as the basis for an elective course in which students develop their research skills).

1. Revolution and Violence

Violence is an integral part of every uprising and coup (in the canonical Soviet version, it was the “heroic” and “historically justified” violence of the oppressed majority). History shows that revolutions are accompanied by a surge of elemental violence. Maxim Gorky described this side of the 1917 revolution in a cycle of essays titled Untimely Thoughts.

The theme of violence provided one of the deepest foundations of Eisenstein’s artistic creativity (see his article, “How I Became a Director (Kak ia stal rezhisserom)”). The film October is shot through with violence, but this theme is dealt with in a very specific way, partly under the influence of social control, partly in alignment the director’s artistic and personal convictions.

Which varieties of violence do we see in October and what has called them forth? The violence of power (the Provisional Government), the violence and cruelty of the city’s inhabitants, the violence of the trappings of the “old world,” violence against the viewer… How do violence and authorial irony work together in the film? What violence does Eisenstein pass over in silence? Which of these types of violence intensified, rather than disappearing, during the Stalin period?

Work on this topic can be conducted through group analysis of relevant excerpts from the film.

2. Reflections on the Nature of the “Dead Regime”

Eisenstein’s film offers a satirical depiction of the Provisional Government, with amateurs playing Kerensky, as well as Lenin. The actor portraying Kerensky, a student who vaguely resembled the politician, overplayed his role, not once changing the dull expression on his face. This did not, however, trouble Eisenstein in the least (we can compare this satirical depiction with various first-hand accounts of Kerensky as a statesman).

The segments of the film featuring Kerensky’s “ascent” up the royal staircase and his recreation in the library of Nicholas II aim to expose Kerensky’s “imperial” lust for power. We find the antithesis of these moments in the final image of the adolescent waif dozing on the tsar’s throne (this shot’s meaning is not as clear-cut as it may seem at first glance).

Yet the elements of the palace’s interior that help to diminish Kerensky’s image could become metaphors for any regime consumed by narcissism. The staircase, “democratic” handshakes with a series of ministers, the comparisons between Napoleon and a peacock—each image is a carefully chosen symbol that could be applied to any dictator or ambitious official.

In working on this theme, the task at hand might be the identification and clarification of the nature of these symbols (metaphorical (peacock), cultural-historical (Napoleon), etc.).

3. October and Soviet Historiography

October laid the foundation for the canonical Soviet version of the history of the revolution. Yet in the process of Stalin’s consolidation of power, the story changed, as theses about Kamenev and Zinoviev’s “treachery” appeared, Trotsky’s role was diminished while Stalin’s grew, and Lenin’s image evolved.

How did October influence Soviet historiography? (Consider heroic pathos, the mass character of the storming of the Winter Palace, the first identification of meaningful events). How does the next anniversary film, Mikhail Romm’s Lenin in October, differ from Eisenstein’s October? (Consider artistic and ideological differences).

These questions could become topics for independent research.

4. The Mechanisms of Agitation and Propaganda

October was created with a great deal of talent, yet much of the film appears to be devoted to straightforward agitation through images and metaphors. The episode with the “Kornilov revolt” aims to discredit the slogan, “for faith, Tsar, and Fatherland,” the theme of the Women’s Battalion discredits the defenders of the Winter Palace, the orators’ appearances at the Congress work to single out the Bolshevik’s speech, the images of the Provisional Government are satirical. Also consider the episode in the Tsarina’s bedroom, the “clock of the whole world,” “the urchin on the throne,” etc.

How is this done? What are the intended interpretations? Which of Eisenstein’s metaphors are clear and can still influence the viewer’s consciousness? Which appear ambiguous or seem to have meanings other than those the director intended? How are these images similar to or different from what we see in advertising today?

Additional Materials:

• Oleg Kovalov, “Ten’, znai svoe mesto! [Phantom, keep your distance!]” (in Russian)

• Naum Kleiman, “Chto modeliruet iskusstvo Eizenshteina? [What shapes Eisenstein’s art?]” (in Russian)

Olga Romanova

Translated by Adrianne Jacobs