Editorial Historical Politics: Memorial Plaques as a Product of “War of Corrections” / Presentation at Non/Fiction 2011

Russia’s current historical politicswith respect to memorial plaques (amendments to legislation, installation of new plaques and repair of old ones, debates and conflicts about their design and content, etc.) is a topic which is monitored daily. Below is a summary of a presentation made at the fair of high-quality books Non/Fiction (December 2011) as part of “Monitoring of Historical Politics” project. It summarizes observations for April –December 2011 and makes a few generalizations.

Source: see messages on “memorial plaque”.

What is interesting about a memorial plaque: It is a brief verbal expression of memory about a person, i.e. who he was, why we should remember him, why this should be remembered and, finally, who “we” are. Importantly, this statement about the past is meant for the routine public urban environment.

Memory among other things is what creates the collectivity of “we,” i.e. our identity. Memory which is presented in statements like “A Great Patriotic War veteran lived in this building” or “A high-profile soviet member of the Communist Party lived in this building” is glue of doubtful viscosity. It is not by chance that this statement is often not addressed to “us” (“we about ourselves”) but to “other people,” such as the “young generation.”

The memorial environment of a city is not homogeneous. There is the center, and there are peripheral areas. The central area includes squares, streets (not necessarily in the downtown neighborhood), facades of buildings, parks, and legends on monuments (regardless of where these monuments are located in terms of their accessibility). The peripheral areas are yards of institutions (archives, schools). There is a field of tension around memorial plaques, e.g., actions are often held in the adjacent area.

An utterance about the past. Memorial plaques highlight (or, as will be seen later, do not highlight but imitate that they do) some places in the city. Most importantly, they utter a certain message about the past. Wording on plaques should always be coordinated with the local government because the utterance is granted the status of the definitive, objective and true statement about the past (urokiistorii.ru/2935 and urokiistorii.ru/1684). It is now more than two years that an 83-year-old retiree from of Essentuki has been trying to have a memorial plaque installed in his town. The plaque commemorates 17 hero Cossacks who had been awarded four crosses of St. George during World War I. Documents have been collected, permit has been obtained from the city government, and a plaque bearing the heroes’ names has been made at the initiator’s cost. But the City Council decided that consent should be obtained from the so-called “registry Cossacks” [Cossacks who are in the government service]. They opposed the idea at first, then they decided that patronymics should be added to names on the plaques, and then the council of atamans [Cossack chiefs] said “it was not reasonable to put another memorial plaque in the Cossack Square.” The initiator retiree went on hunger strike on this occasion

•  Utterances about positive, heroic and glorious past (“military patriotic” purposes): various heroes (Heroes of the Soviet Union, veterans of the Great Patriotic War, war in Afghanistan, war in Chechnya, the 1812 war – Suvorov) (urokiistorii.ru/2935). “Even we do not know much about this [Italian] campaign of Suvorov, and it’s not fashionable at all to speak positively about Russia in Europe, particularly recall that Suvorov’s army helped Italy to win independence. Indeed, even the Holy See continued to exist because of that campaign,” said Vladimir Yakunin, President of Russian Railways, speaking at the ceremony of unveiling a monument to Suvorov in Lomello

Utterances about positive, heroic and glorious past (“military patriotic” purposes): various heroes (Heroes of the Soviet Union, veterans of the Great Patriotic War, war in Afghanistan, war in Chechnya, the 1812 war – Suvorov) (urokiistorii.ru/2935). “Even we do not know much about this [Italian] campaign of Suvorov, and it’s not fashionable at all to speak positively about Russia in Europe, particularly recall that Suvorov’s army helped Italy to win independence. Indeed, even the Holy See continued to exist because of that campaign,” said Vladimir Yakunin, President of Russian Railways, speaking at the ceremony of unveiling a monument to Suvorov in Lomello

At the same time, the urban topographical dimension is not homogeneous: there is the center, and there is the periphery. Differentiation of memory about the past corresponds to this division in that there is memory about more important events/figures and less important ones. The central area includes streets (not only in downtown), squares, parks and facades of buildings. These are places for memory about the Great Patriotic War and official plaques (urokiistorii.ru/2191). The peripheral area includes school walls, for example. Plaques in memory of soldiers who perished in the war in Afghanistan and Chechnya (“Another War”) are often placed there.

Interestingly enough, veterans of “other wars” are perceived as inheritors of the Great Patriotic War veterans at the official level (e.g. by the regional authorities):

“There are increasingly fewer soldiers of the Great Patriotic War who are still alive but veterans of Russia’s contemporary history, which is equally dramatic, have taken the banner of memory from their weakened hands. They know about battles, whiz of bullets and exploding missiles not from hearsay, and they remember friends who died so young! This is why lessons of courage that are held at schools and libraries have become a habitual component of their painstaking activity which is aimed at commemoration of people who had been born on the Kamyshin land, and on developing the young generations” (urokiistorii.ru/2359).

• Utterances about people with “well-established” names, such as historical figures (particularly on the occasion of anniversaries): Stolypin, Gagarin, Solzhenitsyn, men of culture (especially writers) and “outstanding soviet leaders of the Communist Party,” such as secretaries of the oblast-level party committees (urokiistorii.ru/2532, urokiistorii.ru/2427 and urokiistorii.ru/2004). Memorial plaques are usually put up before memorable dates.

Curious cases are often related to the establishment of plaques: for example, a memorial plaque was put up at St. Petersburg plant where Yuri Gagarin took his training as a fitter (urokiistorii.ru/1702); or a memorial plaque in Ufa (urokiistorii.ru/2664) where a well-known writer Sergei Dovlatov lived in 1941-1944 (he was born in Ufa by pure chance because his family had been evacuated to that city); or “memorable cosmic space-related places in Chuvasia (urokiistorii.ru/2337): President of Chuvashia Mikhail Ignatiev said that the third soviet cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolaev (the second monument to him was erected in Cheboksary in September 2011) is “Chuvashia’s national hero and an example from which the young people learn.”

•  Meaningless (imitative) utterances: “A veteran lived in this building: honor, loyalty, duty.” These utterances often couple with imitation of public activism: for example, an initiative group of “guys” decided to put up a commemorative plaque to a veteran, older comrades from the Young Guard and parliamentarians from the United Russia assisted them, and everybody is happy because guided tours will be arranged to see this plaque, and the plaque itself will contribute to the development of the young generation (urokiistorii.ru/2606). The idea can be formulated at the level of micro-history (the wish to put up a plaque in memory of a “rank-and-file nurse”) but it often materializes into plaques that have no content and communicate no information.

Meaningless (imitative) utterances: “A veteran lived in this building: honor, loyalty, duty.” These utterances often couple with imitation of public activism: for example, an initiative group of “guys” decided to put up a commemorative plaque to a veteran, older comrades from the Young Guard and parliamentarians from the United Russia assisted them, and everybody is happy because guided tours will be arranged to see this plaque, and the plaque itself will contribute to the development of the young generation (urokiistorii.ru/2606). The idea can be formulated at the level of micro-history (the wish to put up a plaque in memory of a “rank-and-file nurse”) but it often materializes into plaques that have no content and communicate no information.

• Nondisclosure and gaps in utterances.

|

|

For example, plaques in commemoration of the repressed people do not mention repressions. A plaque in commemoration of poet Pavel Vasiliev was unveiled in March in downtown Moscow (urokiistorii.ru/1693). The poet was shot in 1937 on a fake charge that he intended to kill Stalin. The plaque does not mention three arrests, repression and execution. It only has the poet’s bronze head and inscription “Poet Pavel Nikolaevich Vasiliev lived in this house in 1936-1937.”

The case is the same with a memorial plaque to repressed Turar Ryskulov which was put up in Pokrovsky Boulevard, Moscow, “to honor Russian-Kazakh friendship” (http://urokiistorii.ru/2249). The plaque was initiated and financed by the Kazakh side (Embassy of Kazakhstan). It bears a bas-relief portrait of Ryskulov against the map of the RSFSR but nothing is said about Ryskulov’s tragic fate (repression, execution and rehabilitation). The legend reads, “Turar Ryskulov (1894-1938). Prominent state figure of Kazakhstan and Russia, deputy chairman of Sovnarkom of the RSFSR. Lived in this building in 1931-1934.”

• One-off out-of-context utterances

Complex overlappings of historical memory are reflected on memorial plaques. As a result, wording on such plaques demonstrates a heavy smokescreen of the reason which has brought these plaques into existence. On the other hand, there is the utmost concreteness which is taken out of any context because it turns out that the historical motive cannot be formulated clearly: what is memory about?. Examples:

- A memorial sign was put up in Samara, in a park which commemorates “the parade held on November 7, 1941 in Kuibyshev” (urokiistorii.ru/2494). The decision was taken by the city-level toponymy commission which had been guided by the following logic of discussion: the park commemorates the parade held on November 7, 1941 – the park was named after, or in memory of, the parade – the park commemorating the parade held on November 7, 1941 in Kuibyshev. The revolution of 1917 (on the anniversary of which the parade had been held) is not mentioned at all.

- A plaque commemorating the visit of Emperor Nicholas II to Kaluga in 1904 was put on the façade of a school in Kaluga (urokiistorii.ru/1733). There was no school in this place at that time; instead, there was a large hayfield where the Emperor personally inspired soldiers to win a victory in Russia’s war with Japan. Nicholas II was the only head of state who visited Kaluga in the 20th century. The Emperor and his family were welcomed with music in 1904, so a decision was taken to invite an orchestra to the ceremony of unveiling the plaque. Local scholars helped to reconstruct the atmosphere of the past. According to historians, Nicholas II gave an icon to every soldier. This is why a decision was taken to continue the tradition. School students who demonstrated excellence in competitions in local studies received an icon of Royal Martyrs Tzar Nicholas II and His Family. The unveiling of memorial plaque was part of festivities on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of the House of Romanov.

• Conflict of inscriptions (the typical conflict is between the initiative group and local government). Examples: urokiistorii.ru/1677. A new stand was put up at the Military Cemetery in Tallinn. The monument “To Soldiers Who Perished in World War II,” or “Bronze Soldier,” is now renamed as “Monument to the Soviet Army Soldiers Who Occupied Tallinn on September 22, 1944.” The Tallinn society of WWII veterans has already drafted a protest to the Ministry of Defense, and Embassy of Russia in Estonia sent a diplomatic note to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It should be remembered that the Russian presidential Commission Against the Falsification of History was established largely because the “Bronze Soldier” had been relocated

-

Scandal around the inscription on a monument to the deported Volga Germans in Engels city

Following the logic of symbolic urban topography, memorial plaques on monuments are “central” because they are, in fact, a guide to how a given monument should be perceived because the monument remains an artistic generalization, after all. . The monument was to be erected not in the downtown area but in the courtyard of the city archive (urokiistorii.ru/2279, urokiistorii.ru/2309). When the monument and legend on it had been made as approved by the city government, a representative came from the oblast government. Interestingly enough, the oblast did not provide funding for the monument. The government’s main requirement was to replace “repression” for “deportation” in the legend “To the Russian Germans that were victims of repressions in the USSR.” In the end the monument was erected with the initial legend. - Scandal around the memorial plaque in Katyn (urokiistorii.ru/1698). The Russian authorities replaced the memorial plaque on the memorial stone which was put up in Smolensk, at the place where the Polish delegation died in a plane crash a year ago, so as “not to confuse the two tragedies.” The initial plaque read, “President Kaczyński died on his way to mark the 70th anniversary of the soviet genocide against POW officers of the Polish army” (the plaque was put up by Poland but “had not been coordinated with the oblast government and city authorities”). The new plaque reads, “In memory of 96 Poles headed by President of the Republic of Poland, Lech Kaczyński, who died in a plane crash near Smolensk on April 10, 2010.” The authorities are ready to send the old plaque to Warsaw on request; meanwhile, it is kept at “Katyn,” a museum which commemorates victims of political repressions.

• Actions that are held in relation to memorial plaques reflect disagreement with the wording which is used to describe the past.

-

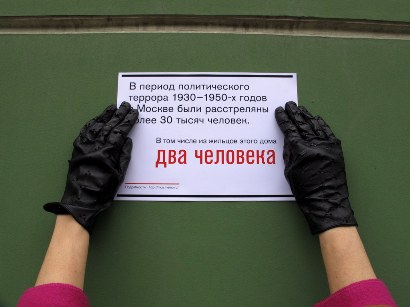

Symbolic plaques are put in memory of the repressed people (urokiistorii.ru/2531). Arkhnadzor and Society Memorial held a joint commemorative action on October 29, on the eve of the Day in Memory of Victims of Political Repressions: hand-made memorial plaques were attached to the walls of houses whose residents had been subject to Stalinist repressions

Symbolic plaques are put in memory of the repressed people (urokiistorii.ru/2531). Arkhnadzor and Society Memorial held a joint commemorative action on October 29, on the eve of the Day in Memory of Victims of Political Repressions: hand-made memorial plaques were attached to the walls of houses whose residents had been subject to Stalinist repressionsContext: we would like to remind that the only plaque which commemorates Muscovites who had been shot is in 13 Maroseika Str., Bldg. 2. Residents of this old house put it in the entrance arch way back in the 1990s. A three-piece plaque reads, “1937-1952. To all those who lived in this house. Who left and did not come back. 1941-1945.” . - A symbolic plaque commemorating Stalin (urokiistorii.ru/1621): “communists of St. Petersburg and Leningrad oblast” attached a bust of Stalin and a memorial plaque to a wall of # 17, 10th Sovetskaya Str. where he lived in 1917-1918.

-

Poems by Brodsky were read out at building which has a plaque to Grigory Romanov, secretary of the Communist Party Committee of Leningrad oblast (urokiistorii.ru/1841). The participants in these readings (that were held on Brodsky’s birthday) chose this method to express their attitude to the authorities’ decision to commemorate Romanov, one of Brodsky’s main persecutors (urokiistorii.ru/2004): “this was how our city marked the 85th birthday of the man whom we would have called our Governor today,” wrote the local media (urokiistorii.ru/1625)

A plaque to Grigory Romanov was put up despite widespread public anger. A decision to place it was taken in 2010, and men of science wrote a letter of protest to the city authorities — they demanded to “immediately recall the disgraceful resolution” about commemoration of the person who “had smothered culture, science, art and freedom, hated intelligentsia and banished actors, poets and artists from the city.” But a “monument to the outstanding secretary of the communist party committee in Rostov oblast” was put up despite protests (urokiistorii.ru/2004): “this was how our city marked the 85th birthday of the man whom we would have called our Governor today,” wrote the local media (urokiistorii.ru/1625). . - A picket was held by communists at a memorial plaque to Boris Yeltsin in Yekaterinburg; they protested against a monument that was to be erected (urokiistorii.ru/1930). The participants announced that they wanted to “unveil their own memorial plaque” to commemorate “their notorious countryman” and remind the authorities and people in Ural about Yeltsin’s guilt in the collapse of the USSR and destructive processes in post-soviet Russia.

Standalone initiatives are cases of alternative motives or alternative expressive means. The logic in the description of a historical event might be the same (“we about them”) or different (“we about ourselves”).

-

A memorial plaque to “Königsberg Jews” (urokiistorii.ru/2085). On June 24, 1942, the SS troops deported Jewish families to a death camp in Maly Trostenets near Minsk, Byelorussia, from the train station in Königsberg (Kaliningrad). The plaque is difficult to read (letters are small; the legend is most likely in two languages) but it has an aesthetically and symbolically remarkable graphics: the Star of David in a crown of thorns.

- A “democratic” plaque in memory of Vladimir Vysotsky is an example of “people’s” plaque (it had been chosen by voting from 12 competition bids). This is a rare case of a plaque which is not “about them” or “about him” but “about us” (urokiistorii.ru/2608). A voting was held in Krasnoyarsk krai to choose the best memorial plaque to Vladimir Vysotsky. It will be placed on the wall of Palace of Culture “Energetic” in Divnogorsk where Vysotsky gave a few concerts in 1968. The competition of plaque designs was initiated by the local urban planning institute Krasnoyarskgrazhdanproject and Divnogorsk city government. The winner plaque shows Vysotsky in a sweater, with a guitar in his hand, walking along the bank of the Yenisei River and looking at the landscape. Other designs are available on the web page of the competition; almost all of them are made in the late soviet style. Interestingly enough, excessively informative plaques (e.g. the one which reads “Vladimir Vysotsky sang in Palace of Culture “Energetic” in August 1968”) were not shortlisted, and the winner design does not have any words at all. It shows only a recognizable landscape and recognizable historical figure whom any local could meet – in theory. The message is: there lived a man named Vysotsky, we all know and love him, he visited this place, and he is the same as we all are.

Paradoxically, the “people’s” memorial plaque is not about an “outstanding person” but about “us” and our common past.

Questions to experts:

- What future do you foresee for our past if things develop as they do (i.e. if tendencies in the placement of memorial plaques continue)?

- What alternatives do you see? If you picture an ideal situation (in terms of opportunities), what memorial plaques would be like?

- How could memory about the “different” past (i.e. not about the “positive” or “outstanding” past) be reflected on plaques?

- What are practices of making memorial plaques in Europe and the USA?

Written by: Yulia Chernikova