Speech by the Chair of International Memorial Society at the Custodian of National Memory Award Ceremony

On 31st May 2012, the Royal Castle in Warsaw hosted the award ceremony for winners of the Custodian of National Memory (Kustosz Pamięci Narodowej) prize. This prize has been awarded since 2002 by the Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej) to organisations, institutions and individuals who play an active role in preserving the memory of the Polish people in the period between 1939-1989. This year the Jury awarded the title of Custodian of National Memory to, amongst others, the Memorial Historical, Educational, Human Rights And Charitable Society (you can read about the other 2012 prize-winners here).

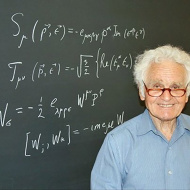

The Chair of Memorial International, Arseny Roginsky, gave the following acceptance speech at the award ceremony

Ladies and gentlemen,

Dear friends,

On behalf of the International Memorial Society, I would like to thank the jury of the Custodian of National Memory prize for awarding the prize to our Society.

Memory of the past is the basis for any national consciousness, and this is particularly in evidence in Poland.

The Memorial Society has been working on the topic of Poland for many years. It has been studying the history of repression against the Poles and Polish citizens (one of the first collections of research papers published by Memorial was called just that, Repression against Poles and citizens of Poland). It has gathered information on the lives of tens of thousands of Polish people, which were ruined or ended in the Stalinist meat-grinder. The knowledge uncovered by Memorial’s researchers is becoming a part of both the Polish and Russian memory.

So why do we focus so much attention on Poland in our work?

We do so because the image of Poland that has formed in the Russian national memory, in the Russian national consciousness, represents a particular cultural phenomenon that plays an extremely important role in modern Russia.

There are several reasons why Poland is of special importance to Russia, but I will only touch upon two. Firstly, there is the ‘Polish myth’ in the Soviet cultural consciousness between the 1950s and 1970s. And secondly, the way events related to Poland entwined in our history have been turned into a symbolic gauge, a kind of litmus test for defining positions in the fierce social debate over our own Russian and Soviet history.

The history of the ‘Polish myth’ dates back as far as Alexander Herzen, and it has become firmly entrenched in Russian cultural tradition. This sees in Poland the tragic and heroic image of an eternal rebel and an eternal victim of Russian imperialism, from Kościuszko through to the Red Army. Given this perception, the Russian recollection of the Soviet terror against the Polish people normally goes hand in hand with the concept of Russia’s two centuries of historical guilt in relation to Poland and, at the same time, the idea of the metaphysical guilt Russia feels for itself.

From the second half of the 1950s, this ‘Polish myth’ gained an additional cultural component in the Russian national consciousness. People within Russia were particularly drawn to poetry and prose by Polish writers from the war generation, Polish cinema, works by leading Polish artists, treatises by Polish sociologists, and the semi-independent journals which began to appear in Poland at the end of the 1950s. In political terms, the image of a fighting Poland was formed during the ‘Polish October’ of 1956 and the ‘Polish March’ of 1968, the strikes of 1976, the activities of the Workers’ Defence Committee and Committee for Social Self-defence (KOS-KOR), the Solidarity revolution and so on. This image, which prevailed predominantly (but not exclusively) among the Soviet liberal intelligentsia, represented nothing more than the echo of something that had never come into existence — everything that occurred in Polish culture and in Polish society, and did not occur (or began but was quickly stifled at its roots) in Soviet culture and Soviet society.

However, during the last two decades this image of Poland has been put on the back burner, due to competition from another image — Poland as the object of tough historical discussion in post-Soviet Russian society.

The pivotal topic for these discussions is the events of 1939-1940.

Despite the extremes in evaluations of historical events, these particular events — the secret additional protocol to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the Red Army crossing the USSR-Poland border on 17th September 1939, the fervour of the heroic and futile fight of the Polish army against the Nazis, the massacre of Polish prisoners of war at Katyn, Kalinin and Kharkiv — are gradually becoming common historical knowledge.

We’re not talking about the facts – nowadays not many people try to deny these. The issue is with the way the information is interpreted and evaluated. For want of better reasoning, Russian ‘great power nationalists’ and ‘national patriots’ go as far as to proclaim that Katyn a “justifiable response” to the death of members of the Soviet Red Army in Polish prisoner of war camps in 1920-1921, or start harking back to grievances from the 17th century.

At the same time, their opponents, including Memorial, are trying to develop joint approaches to Russian-Polish history, which rather than causing divisions can unite and reconcile us and our neighbours. Not just with Poles, but also with Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Georgians and all the rest.

We are trying to ensure Russian citizens fully understand the scale of the Polish tragedy in the 20th century and accept this tragedy as a part of their own history.

This work should be based mainly on memory — the specific personal and family recollections of people living in North-West Russia, the Urals, Siberia and Kazakhstan. This memory is pushing dozens of people in the provinces to search out and record the remains of designated Polish settlements in the Taiga and abandoned Polish cemeteries, and to gather the stories of local, long-time residents about their connection with Poland. This memory is also alive amongst the younger generations. The research by senior high school students submitted every year to Memorial’s Russia-wide competition The Person in History. 20th Century Russia (in fact, the idea for this competition came from Karta, our colleagues from Warsaw) always includes several papers connected to the ‘Polish footprint’ in the regions of Russia.

Memorial is not renouncing the fervour for Poland of the 1960s USSR. And although we appreciate all the clichés inherent in the myth, we don’t want to completely forget the romantic image of Poland we held in our youth — why should we? During the last six months we have seen how unexpectedly, and seemingly out of nothing, the spirit of the sixties can be resurrected in the streets and squares of Moscow, amongst not even the children, but the grandchildren and great grandchildren of the people of the 1960s. In one form or another, I don’t think that the resurrection of the ‘Polish myth’ has bypassed the consciousness of the younger generations either.

But during two decades of working on Soviet history we have gradually moved away from the 1960s concept of metaphysical national guilt felt by one people towards another, and the similar metaphysical guilt felt by a people in relation to itself. We have, in general, moved away from the notion of ‘collective guilt’ altogether — these ideas do not fit with the modern understanding of freedom and human dignity. We are not motivated in our work by a feeling of collective guilt, but rather a consciousness of the individual civic responsibility that each of us bears for the events that happened many decades ago, including events that occurred before our time, during the time of our parents, grandparents and great grandparents, in the same way that each of us has a civic responsibility for the things happening in our country today.

Or rather, not each of us, but only those who agree to shoulder this responsibility. Those for whom historical heritage is not an empty sound, nor a check-list of great victories and achievements, but instead represents national history as a whole, with all its successes and disasters, glory and shame.

We believe that one shouldn’t look in history for guilt — either another’s or one’s own — but rather for an understanding of the tragedies of the past and recognition of one’s own responsibility for them.

We would like our relationship with the past to be shared by as many of our fellow citizens as possible.

We would like this relationship with our own national history to gradually develop amongst our neighbours too.

Perhaps this approach will at some point allow us to arrive at a common memory of a common past”.

Source: