«The Deported Childhood»: How the Historical and Documentary Exhibition Is Made

A “historical and documentary” (as it was called by the organizing team) exhibition “The Deported Childhood: the Lives of Children Deported to Latvia, 1943 – 1944” was held at the State Museum of Contemporary History of Russia for less than a month, from January 19 through February 15, 2012. But this short time was enough for the scandal – including a diplomatic one – to flare up around it: Latvia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs came up with severe criticism, and the Government of Latvia declared the organizers as personas non grata. Interestingly enough, references in the media, blogs and statements made by the parties do not describe the exhibition itself, and the story does not go beyond the discussion of historical policy in general and historical policy in the present-day Latvia in particular. Urokiistorii visited the museum when the exhibition was open; it turned out that the historical & documentary exhibition is short of both history and documents.

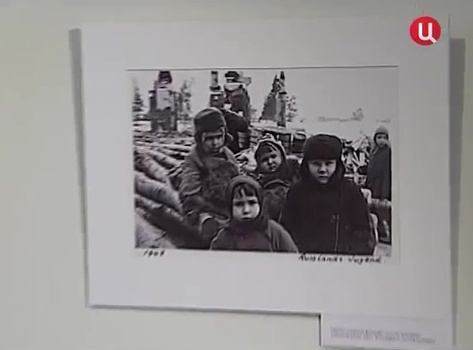

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The photographs were taken from Channel TVC's report about the exhibition |

Although not many people visited the exhibition and it was displayed in a somewhat funny environment – right after a New Year display of soviet toys, – its institutional message is obvious. A “historical & documentary exhibition” in the state-run historical museum is a fact which is difficult to challenge after it is over. Few people are likely to turn to its contents and subject post factum; similarly, a post-graduate student would be introduced as a “Ph.D. holder” right after he/she has defended the dissertation, and nobody would go into detail as to the topic or logic of the paper. In the same way, when references are made the discussions focus on the Latvian Government’s ban on the entry of non grata “Russian historians,” Latvia’s annoyance with the presentation of “historical and documentary facts” and the refusal to display these same facts and a “historical exhibition” in Latvia

Below we tried to describe this exhibition which the “Historical Memory” foundation and the State Museum of Contemporary History of Russia had built as part of the program “Increasing the Status of People Who Lived in the Burned Byelorussian Villages” (its idea had been suggested by Alexander Dyukov and Olesya Orlenko). We also tried to formulate questions that it brought about. We hope the reader will be able to make all the necessary conclusions on his own.

The exhibition was held in two small halls and consisted of four parts.

The first and, probably, the most important part is the introductory text (it is cited below in full) which gives the visitor some historical information. The text is very explicit in its assessments and guidance (“Latvian collaborationism,” punitive operations, “corpses of children,” slaving on Latvian peasants, and the present-day immoral historical policy in Latvia where the “survived children who were victims of Nazism, as well as their children and grandchildren, received the status of ‘non-citizens’ and are treated as ‘soviet civil occupants’ by the local nationalist-minded establishment”). But the text is obviously short of input data. Instead of a coherent story, it offers a set of statements and hints from which one can only understand that:

- Latvians took part in punitive operations carried out by the Nazis during World War II (unasked and unanswered questions: who exactly took part in them, how many people participated, how this happened, what were the sources, and how did collaboration with the fascist army develop in other countries and in the republics of the USSR?);

- People from the occupied territories (Russians, Poles, Byelorussians) were deported for forced labor “to Latvia and Germany” (the countries are named in exactly this sequence; this gives an impression that during World War II Latvia was not an occupied territory but came short of being Germany’s partner and ally. Unasked and unanswered questions: what was the history of forced labor and Ostarbeiters, how were they distributed for labor across Germany during the occupation, in what countries and types of labor did Ostarbeiters work, and what were their life experiences during and after the war?);

- Nazi concentration camp Salaspils worked in Latvia; Nazis made cruel experiments on children who had been deported from Russia, and used them as laborers (unasked and unanswered questions: what was the history of this camp, how did German organizers and administrators cooperate with the Latvian staff, what were the common operating procedures of the fascist labor camps and death camps that were established almost entirely outside Germany – in Eastern Europe; who were Salaspils prisoners (most of them were Latvian and Russian political prisoners who were suspected of having contacts with partisans, as well as European Jews, soviet POWs and civilians suspected of contacts with partisans)?);

- The authorities (elite) of the present-day Latvia consist of bad people who are, in fact, very similar to those Latvian punishers that acted during World War II.

The main characters of this introductory text and, indeed, of the whole exhibition are not children who had been deported to Latvia, as could have been expected from its name (unasked and unanswered questions: where were they deported from, how many, were they deported to Latvia only?). Its main characters are abstract Nazis who look not so bad against the background of their blood-thirsty assistants, and bad Latvian guys that are taken out of any real historical context and exist in the air-free space of moral judgments.

We would like to avoid being misunderstood: we would not dare to exculpate Nazi (and any other) punishers and Latvian (and any other) aides and policemen. We certainly do not say that they did not exist – they did! But one would expect that a “historical & documentary” exhibition would present a more coherent story about historical events, their origins, sources, implications and contexts.

The second part of the exhibition is a series of documentary photos (as is said in legends, mostly from the archives of German soldiers) that show burning Byelorussian villages. This series also includes several photos of refugee children from the war zone, and the barbed-wire fence of Salaspils camp. The burning Byelorussian villages which Fascist soldiers incinerated for the villagers’ real or alleged contacts with the partisans are certainly tragic but not new. The authors of the exhibition say that Latvians took part in the punitive operations; quite possibly, but one would also like to know who exactly and how many Latvians took part in such operations, where this is known from, and how this information relates to the photos that were displayed – they show smoke on the background, and the German photographer’s writing in the bottom “Retribution to bandits.” What do photos of Salaspils, a Fascist camp that was established close to Riga and became the central concentration camp for the whole occupied territory of Eastern Europe, tell the visitor about – that the camp was on the territory of Latvia? Well, Oswiecim was on the territory of Poland, and what follows from this?

The third and forth parts of the exhibition include videos of oral stories told by the former Salaspils prisoners. People speaking about their past experiences are videoed against the background of large artistic photos of a snowbound soviet-time memorial (it was unveiled in 1967) at the place where the camp was located. The videos last for about 15 minutes in total. Witnesses recall how they lived in the camp and how they worked for Latvian peasants: they were cleaners and babysitters, and tended the kitchen gardens. All this is displayed without any historical context whatever (e.g. a story about history of forced labor in general and the concentration camp in particular) but with large artistic strokes and explicit allusions, such as fluffy snow on the photos of the soviet memorial and soaked children’s toys at the bottom of the giant sculpture.

While going around the exhibition, a visitor tries to get answers to such questions as what this story is about, when it began, what it ended with and who took part in it. But he finds huge gaps and missing contexts in its narration – and he soon realizes that there seem to be no narration at all. Instead, there is an accused, there are patched-up pieces of an investigation case and a rehearsal of a court trial which is intricately woven in such a way that every visitor acts as a witness simply because he showed up at the appointed place at the appointed time – at a “historical & documentary exhibition” in the state-run museum of contemporary history. But the case seems to be falling apart even despite the international response. It’s OK with the prosecution part but it’s not very much OK with the evidence of crime.

Schedule: text of the exhibition

The Deported Childhood: the Lives of Children Deported to Latvia in 1943-1944/ historical & documentary exhibition

“In 1943-1944 Nazis carried out mass-scale punitive operations in the Russian and Byelorussian regions that neighbored on Latvia and Latvian collaborationist units were often the spearhead of these operations.

A strip of burned-over land along the borderline was created: villages were burned down, and their population – Russians, Poles and Byelorussians – was partially killed and partially deported to Latvia and Germany for forced labor.

The punishers’ procedures are described in a letter from Otto Drexler, Commissioner General for Riga (the letter is dated in summer 1943): “The campaign developed as follows: when a unit entered a village (there was no resistance at first), it immediately shot those who were suspected of partisan activities. Almost all men from 16 to 50 years old fell into this category. … Right after (the army troops) an SD team came and acted approximately as follows: it shot all other suspects. The rest, mostly locals and children, were to go through the so-called “second filtration.” Those who were unable to continue walking were shot. Villages were pillaged and burned even before the arrival of administrative teams whose task was to take valuables out to a safe place.” The procedure described by Drexler corresponded to what happened in reality, as is proven by the fate of Rositsa village and neighboring villages that were exterminated in February 1943. Contrary to intelligence information of the Germans (according to which Rositsa was a place where “bandits” gathered), there were no partisans in this village. Yet, a quick-action SD team killed 206 villagers. Besides, Rositsa was a place to which people from the neighboring villages were driven for “second filtration.” Some of them were later thrown into concentration camp Salaspils not far from to Riga, and others were burned down in the local Roman Catholic church together with two priests.

The deported people had tragic fates. Many of them were unable to survive victimization, deprivations and illnesses. Investigation testimonies of A. Hartmansis, collaborationists’ aide, describe horrendous procedures of massacres and coercion to forced labor. “Some of the survived people were later brought to Salaspils camp. Husbands were separated from wives, and then they were all taken to forced slave labor to Germany; children were forcibly taken away from parents, and some of them were distributed among citizens of Latvia but most children were so atrophic that almost all of them died of illnesses.”

Latvian peasants bought little laborers for 9-15 German occupation marks per month. Some farmers tried to squeeze out as much as possible from small children for this money. For example, in its internal document dated October 2, 1943 the Children Registration Point in Riga stated, “Small children of Russian refugees work for farmers and do work that does not correspond to their age, … without any rest, from early morning till late night, in rags, shoeless, with very sparse feeding, often unfed for a few days, sick, without any medical aid. Their owners went so far in their cruelty that they beat these miserable children who are unable to work because of hunger … they are robbed of the remaining things … when they cannot work because of sickness they are not fed at all, and they have to sleep in kitchens on dirty floors.” Of course, not all Latvian farmers treated the children in this way but many Latvians directly benefited from punitive operations in which Latvian policemen took part and which turned into slave-hunting.

The “unsold” children (including infants) were kept in Salaspils camp separately from adult prisoners. Girls aged 5 to 7 had to take care of babies. Every day the camp guards carried out large baskets that were full of stiff corpses of dead children. Corpses were thrown into cesspits, burned down outside the camp or buried in the forest next to the camp <compare the text from Wikipedia: “Every day the camp guards carried out large baskets that were full of stiff corpses of children who had died tormenting death. They were burned down outside the camp fence or thrown into cesspits, and some of them were buried in the forest not far from the camp.”>. “Medical experiments” made by the German Nazi “doctors” also contributed to the high death rate of small prisoners of Salaspils.

After the war, many children who were lucky to survive stayed in Latvia and grew up there, either in orphanages or in foster families, because they had nowhere to go: their villages had been burned down, and their parents had been killed or missing during the war. The survivor children who were victims of Nazism, as well as their children and grandchildren, received the status of “noncitizens” in the present-day Latvia, and the local nationalistic establishment treats them as ‘”soviet civil occupants.’ Their political and civil rights are restricted, while their tormentors – Latvian collaborationists – are treated as heroes.”

Related to this topic:

News about the exhibition and a scandal related to it: 1, 2, 3, 4 / urokiistorii

- History of camp in Salaspils / information, documents, research (including detailed information about the camp)

- about memorial in Salaspils (unveiled in 1967); see also an article about the memorial in the Large Soviet Encyclopedia

- song “Zakhlebnulsya detskiy krik. I rastayal, slovno ekho [A child’s cry stifled and died out as if an echo] (“Singing Guitars” group) / soviet music (+VIDEO)

- A biased article about Latvian historical memory toward the memorial complex

- RVC channel’s report about the exhibition (interestingly enough, the registration card of Anna Frank was presented in a story about children who were prisoners in Salaspils)

- The U. S. Ambassador at the exhibition / photo report

- Interview about the exhibition with Dyukov

The exhibition was visited by Yulia Chernikova

Translated by Marina Burkova