ru_lenin: Sculptural Leniniana

The LiveJournal community “Monuments to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin” features what is probably the most complete thematic catalog of photographs of monuments to Lenin currently available. The community’s creators intend “to collect ALL of the monuments to V. I. Lenin erected on the territory of the republics of the former USSR, and those located in countries in other countries around the world.” As of July 2009, information on 3500 items was already available. The collection is updated on an ongoing basis.

The ru_lenin Community

Through the ru_lenin community’s profile, you can browse the monuments by country, city, or region. The largest collection contains photographs of monuments located in Russian territory (almost 2300 monuments). You can also see images of monuments scattered throughout Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, the Caucasus region and Central Asia, the Baltic region, and Moldova, as well as further abroad.

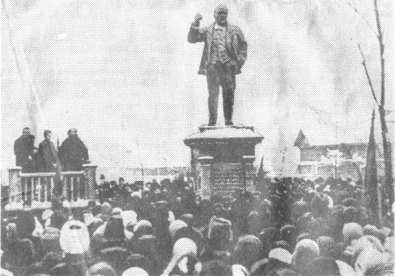

A standard post is comprised of photographs of a monument, as precise as possible an indication of the monument’s location and, in some cases, a short commentary. Visitors to the site will also encounter archival images, such as the illustration accompanying the article “From Village Workers to Ilyich” (monuments from the 1920s-30s). Additionally, visitors can read genuine research, as in the posts titled “Monumental Leniniana’s First Steps: Monuments to V. I. Lenin, 1918-1925” and “The First Monument to the Leader in Petersburg.”

Monumental Propaganda and Images of Lenin

“Lenin himself embodied concentrated rays of light and heat, broad waves, which are flowing now over the land in the heroism of common workers, peasants, and Red Army soldiers. We are stepping into a heroic epoch, and the quintessence of this era, its brightest point, its concentration—Lenin—should inspire and elevate us also in that art we are called upon to create.”

A. V. Lunacharsky

The idea of monumental propaganda (intentionally using specially-built monuments to influence people and the communication of specific messages to the public) came about during Lenin’s life. On April 12, 1918, the Council of People’s Commissars put forth a decree titled “About the Republic’s Monuments.” Later it came to be known as the “plan for monumental propaganda.” The image of the revolutionary and leader emerged as monumental propaganda’s central character, a figure meant to inspire his fellow countrymen

The image of Lenin embodied in these sculptural memorials changed over the course of the Soviet period. The Lenin’s figure’s status changed within the system of ideology, propaganda, and education—accordingly, a range of Lenin’s characteristics were highlighted. In the 1920s, before the canon had truly coalesced, monuments were dedicated to “Dear Ilyich.” These demanded the image of a “living” Lenin, representing him as his contemporaries had known him

On January 26, 1924, after Lenin’s death, the Congress of Soviets put forth a decree, “On the Construction of Monuments to V. I. Lenin,” which started a massive, statewide process of Leninization. The 1930s-1950s saw the spread of images of “Lenin as Leader” and many more or less identical sculptures of Lenin appeared in different cities. Often these were duplicates made from relatively non-durable materials [1]. It was during this period that the image of Lenin developed its particular theatricality and artificiality, which is reflected in his tense and unnatural pose (the leader showing his people the path), in the gesture of his outstretched hand (pointing to the bright future), and the repetitive details of his clothing (his cap, his coat blowing open). This period also saw the appearance of a series of sculptures that recreated images of Lenin in daily life (“Grandfather Lenin,” “Lenin, the Friend of the Children,” young Lenin), but these did not occupy the more significant and visible parts of the cities, rather they remained tucked away in parks, at Young Pioneer camps, and at memorial sites. During these years monuments to Stalin were also erected; they were later torn down, after the cult of personality was denounced [1].

Beginning in the 1960s, after the “return to Leninist norms” (see P. Vail and A. Genis, 60-e. Mir sovetskogo cheloveka [The 1960s: The World of the Soviet People]), new conceptual principles took shape, inspired by the renewal of communist ideas and by competitions for the creation of monuments to Lenin (in 1958, 1959, and 1966). A large number of memorials were constructed in honor of key events during the 1960s, first Lenin’s 90th birthday (1960) and, later in the decade, Lenin’s 100th birthday and the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. On the one hand, during this period Lenin’s image became more concrete, more private, as the “life-like” Lenin of the 1920s merged with the “heroism” of the 1930s-1950s to become the figure of the “living hero”: Lenin grew smaller, he sat down to rest, thoughtfully reflecting, squinting cleverly, etc.

On the other hand, an opposing tendency was also at work, as some portrait memorials were transformed by symbols (of country, time, socialism). These are characterized by imprecisely formed granite masses or symbolic figures, such as a globe, attention to the geometry of the pedestal, the inclusion of architectural elements, and an eloquent laconicism. Lenin’s head often takes the place of his entire figure [2].

On the other hand, an opposing tendency was also at work, as some portrait memorials were transformed by symbols (of country, time, socialism). These are characterized by imprecisely formed granite masses or symbolic figures, such as a globe, attention to the geometry of the pedestal, the inclusion of architectural elements, and an eloquent laconicism. Lenin’s head often takes the place of his entire figure [2].

The image of Lenin in monumental art did not exist or evolve in isolation. Monuments to Lenin are intimately linked to the urban space. They stood in squares, regions, and cities. Rituals formed around them. In these spaces demonstrations and folk festivals took place; school children became Young Pioneers; newlyweds strolled there after their weddings. In these spaces, private meetings and visitors’ tours began.

Lenin Lives?

Beginning in the mid-1980s Lenin’s image, along with other communist symbols, came to be used widely in sots-art (social art) in an ironic, grotesque artistic dialogue with Soviet mass art. Leonid Sokov’s 1984 work, “A Meeting of Two Sculptures (Lenin and Giacometti),” became one of the most famous pieces to emerge from this movement. In this sculpture, a realistic image of Lenin appears in an aesthetic context unfamiliar to him, momentarily losing the propaganda message that had developed over the decades, becoming simply an art object.

Beginning in the mid-1980s Lenin’s image, along with other communist symbols, came to be used widely in sots-art (social art) in an ironic, grotesque artistic dialogue with Soviet mass art. Leonid Sokov’s 1984 work, “A Meeting of Two Sculptures (Lenin and Giacometti),” became one of the most famous pieces to emerge from this movement. In this sculpture, a realistic image of Lenin appears in an aesthetic context unfamiliar to him, momentarily losing the propaganda message that had developed over the decades, becoming simply an art object.

The current status of the many monuments to Lenin that still exist is far from certain. Some of them are lost in city courtyards or overgrown parks, appearing as the fragments of a vanishing empire.

The majority remain in their former homes in Russian cities, in central squares, but are, in a way, simultaneously excluded from the public space, becoming visible only during communists’ infrequent demonstrations or in the course of incidents of vandalism (see the list of ruined monuments to Lenin on Wikipedia).

The majority remain in their former homes in Russian cities, in central squares, but are, in a way, simultaneously excluded from the public space, becoming visible only during communists’ infrequent demonstrations or in the course of incidents of vandalism (see the list of ruined monuments to Lenin on Wikipedia).

It is curious that, in Moscow, a triangle can be drawn between the Church of Christ the Savior, the Kremlin, and the Pushkin memorial, which serves in this case as a monument to Lenin.

The majority remain in their former homes in Russian cities, in central squares, but are, in a way, simultaneously excluded from the public space, becoming visible only during communists’ infrequent demonstrations or in the course of incidents of vandalism (see the list of ruined monuments to Lenin on Wikipedia).

Yet, even being invisible, the Lenin monument functions, together with the administrative building and the church, as one of the three pinnacles or cornerstones of the modern city’s symbolic center (this is especially the case in smaller cities). These sites can be tentatively marked as “the presence of the past,” “the essential and earthly,” and “the spiritual.”

It is curious that, in Moscow, a triangle can be drawn between the Church of Christ the Savior, the Kremlin, and the Pushkin memorial, which serves in this case as a monument to Lenin.

It is curious that, in Moscow, a triangle can be drawn between the Church of Christ the Savior, the Kremlin, and the Pushkin memorial, which serves in this case as a monument to Lenin.

Additional Links:

- Collection of photographs of monuments to Lenin

- Monuments to Lenin located in Belarus

- ru_monument—a community dedicated to “all types of monuments, from memorial complexes to memorial symbols”

- Monumental propaganda, an article from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd edition, 1969-1978

- Zimenko, V. M. Obraz velikogo Lenina v proizvedeniiakh sovetskogo izobrazitel’nogo iskusstva [The Image of the Great Lenin in Works of Soviet Graphic Art], Moscow, 1962, with illustrations.

- Zelinskii, K. “Ideologiia i zadachy sovetskoi arkhitektury [Ideology and the Aims of Soviet Architecture],” the original article about Soviet architecture (and Soviet monumental propaganda)

- Obraz V. I. Lenina v narodnom i dekorativno-prikladnom iskusstve Rossiiskoi Federatsii [The Image of V. I. Lenin in Folk and Decorative-Applied Art in the Russian Federation], Moscow, 1969

- Iakhont, O. Sovetskaia skul’ptura [Soviet Sculpture], Moscow, 1973, “Leniniana” Division

- Article about monuments to Lenin on Wikipedia

- Another report on the exhibition, “Lenin from A to Z”

- Article “Sovetskii mif o Lenine [The Soviet Myth of Lenin]” on History Lessons

Yulia Chernikova

Translated by Adrianne Jacobs