Archival Research in a Time of Restrictions: Why it’s become Dangerous for Historians to Work in Archives

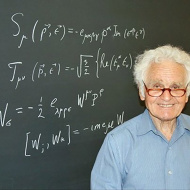

Historian Nikita Petrov discusses conditions for historians working in archives today, while their colleagues in Archangelsk stand trial and the CIS considers adopting a uniform archival policy prohibiting the declassification of personal information. Could historians lose their profession, their freedom, or both?

Nikita Petrov – historian and doctor of philosophy affiliated with the humanitarian society Memorial.

– As we speak, Mikhail Suprun, a historian and archival researcher, is on trial in Archangelsk. He is accused of committing violations of privacy by gathering information about victims of repression. Is this matter affecting other historians who, on account of the nature of their profession, do archival work?

– If we trace how the criminal case has unfolded, leaving aside both protests by Russian historians (there has been little reaction to their open letter) and also protests in other countries, we can see that this is a demonstration of sorts, punishment is not the central issue. Even if both of the accused (MVD officer Aleksandr Dudarev is also on trial for having allowed the historian into the archive) are cleared of the charges, this is still a bad precedent, and it is changing the climate surrounding access archival holdings. This has already frightened historians and workers in state and institutional archives. It now appears possible for any historian’s life to be ruined. This does not mean that all historians are going to be arrested tomorrow, but a message has been sent.

– What kind of message? What is the charge against Suprun and, by extension, other Russian historians engaged in gathering factual (and that includes personal) information?

– Article 137 of the Russian Criminal Code (Invasion of Personal Privacy), under which Suprun has been charged, is in itself extremely foggy and vague.

Part 1, article 137 CCRF describes “Illegal collection or spreading of information about the private life of a person which constitutes his personal or family secrets, without his consent, or the distribution of this information in a public speech, in a publicly performed work, or in the mass media.” Yet we don’t have a precise definition of ‘personal secret’. This kind of thing probably wouldn’t happen in Moscow. All the same it’s been quite noisy. Archangelsk has become a test site. I don’t think that any high-level government official has made a decree about prosecuting historians and sealing the archives. This is probably an independent action on the part of local, regional officials, but they know the current atmosphere. The mood in academic circles was already sombre and pessimistic when it came to archival work. We not only see that the authorities’ are reluctant to open archives and declassify information, we also sense the absence of an effort to understand the past. There have, of course, been declarations, announcements, statements about the importance of historical knowledge, about overcoming the totalitarian past, but none of this has resulted in anything concrete. Reality, for example this criminal case, completely contradicts such pronouncements. Russia appears to be experiencing perestroika in reverse, moving from freedom to restriction, from permissions to prohibitions, from clear, straightforward speech to allusions and self-censorship. Historians also engage in self-censorship. They understand that it isn’t worth the risk to write about certain topics, even though they aren’t technically off-limits.

– Recently another archival “affair” has come to light: there has been a certain agreement on a uniform archival policy within the CIS. What can we expect from this initiative?

– After 1991 each former Soviet state had its own archival policy, its own law. Within the CIS, there have already been bilateral attempts to regulate and coordinate the declassification of Soviet documents. In reality, such agreements aim to limit declassification. For example, on January 20, 2003 Russia and Belarus signed a joint agreement on the declassification of archival materials.

The new and more far-reaching agreement is the Protocol for the Procedure for Review of the Classification Level of Information Classified in the USSR Period in CIS Countries. As far as I know, Belarus, Armenia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan have already signed on. Ukraine and Moldova have not yet signed, and I very much hope that they will not. Ukrainian historians came out in sharp opposition and Ukraine put on the brakes. The Ukrainian situation is amusing. Ukraine has existed as a state since 1991, which means that no Ukrainian laws have any bearing on pre-1991 matters. This means the seals the Ukrainian government has placed on documents created before 1991 are senseless and illegal; the national law on state secrets does not apply to materials produced by another state, the USSR. Ukrainian archives house many interesting documents. It’s no coincidence that foreign historians studying the Soviet period prefer to work in Ukraine, Bishkek, or Baku, where they can gain access to archives much more easily than in Russia. At the very least, that’s what the situation has been. As for Russian historians, I haven’t heard anything about their protests, and this is understandable. We’ve become far too accustomed to political restrictions. It is difficult to imagine that historians will go out and protest in the streets.

The agreement was signed in October 2011 at the CIS summit in St. Petersburg and it sets out orders regarding the proper handling of classified documents. The text was not available on the Internet for some time, but it has appeared recently. I suspect that there are also ‘secret protocols’, guidelines for putting it into action, because in and of itself the text of the agreement is too vague, it doesn’t describe anything concrete. The central point is this: documents classified during the Soviet period can be declassified only with the permission of all of relevant parties and countries. In reality this reflects the imperial ambitions of Moscow and the Kremlin; declassification relies first of all on Moscow's cooperation. It involves all of the structures that protect state secrets. Russia has the Interdepartmental Commission for the Protection of State Secrets and all of the CIS countries, since they have existed independently for some time now, possess similar organs.

Formally, it is not an ideological document (our constitution prohibits a uniform state ideology). It is impossible to challenge it in court. Yet it functions, of course, in precisely that way. It’s clear that there is certain information about the actions of Soviet government that the Kremlin does not want made public. And again, as in the case of the Suprun affair, the most important thing is that it demonstrates the politics of prohibition. We don't know how it will work out in practice, it’s quite possible that the CIS countries will continue to publish documents, but we can clearly see where this road will lead. Just as in the past, Moscow is trying to control everything.

– Could limiting access to archives impact historical research and representations of the past?

– At the present, probably not. Too much has already been published. I have in mind not only research, but also multi-volume collections of documents. Even if every archive in Russia closed indefinitely “for cleaning” and refused to let anyone in, we could still look at what has already been published and see quite clearly that the Soviet regime was criminal. The problem is not that the documents are few. The problem is that they’ve not been made sense of, even by historians. Officials remain unaware of them for a long time, trying all the while to hide information that we’ve already discovered in the archives.

But, what can you say? A historian without an archive isn’t a historian. A researcher, investigating a specific topic, always yearns to find some archival gem in the course of his work. He will probably not face a direct refusal even now, but he can expect formalities that will complicate acquiring archival materials, delays and bureaucratic obstacles. These are tiresome but hardly insurmountable.

Interview by Yulia Chernikova

Translated by Adrianne Jacobs